test blog

Month: June 2018

What is Mature-Buck-Effective? Deer Hunters, Don’t Miss Reading This Blog

Mature bucks 3-1/2 to 6-1/2 years of age are the most elusive and most wasted of whitetails during deer hunting seasons. The reason is, there is hardly a whitetail buck anywhere in America today that has survived three or more hunting seasons that does not know exactly how to safely locate, identify and avoid hunters making drives, hunters moving about on foot in search of deer and hunters using elevated or ground level stands. Dr. Ken Nordberg’s six new hunting methods, ranging in complexity from simple portable stump hunting to opportunistic stand hunting were specificlly designed to hunt such deer. All are mature-buck-effective and fair chase (no bait) hunting methods. Between 1990 and 2017 these hunting methods enabled Doc and his three sons to take 98 mature bucks on public land with low deer numbers and overabundant wolves, their best buck hunting ever.

Unlike back in the 1980s when newly introduced portable tree stands and doe-in-heat buck lures combined to launch two decades of unusually easy buck hunting, no new hunting aid is available today that can make it happen again. Our only salvation as deer hunters today is more knowedgeable and skillful deer hunting, mature-buck-effective hunting methods if you’d like to regularly take mature bucks. To be mature-buck-effectice, Dr. Nordberg’s new hunting methods include the follow key elements.

At the top of the list are special elevated or ground level stand sites…

- Used one day or half day for the first time ever (most productive for for taking older bucks), used one day or half day per hunting season during multiple years, sometimes used an additional day or half day 4–7 days later per hunting season (for good reasons only).

- At a site or in a tree tree providing superior human-silhouette masking natural and unaltered cover (no man-made shooting lane) requiring little or no preparation or preparation time.

- Can be approached without being positively identified by nearby deer.

- Located within easy shooting distance downwind or crosswind of freshly made tracks and/or droppings made by a mature walking (unalarmed) buck in or near a whitetail feeding area (graze or browse) – the one area in which whitetails are most predictable, most easily seen and easiest targets.

- Located within sight of fresh tracks of a buck that dragged its hooves from track to track in snow (under the influence of airborne doe in heat pheromone) in or adjacent to a feeding area or doe bedding area (must be stand hunted very soon).

- Located within sight of lots of fresh droppings made by yearling and/or mature does in or near a feeding area when or where no snow covers the ground.

- Located within sight downwind or crosswind of a freshly made or renewed buck ground scrape not approached within 10–20 yards by a hunter.

- Located 10–20 yards back in timber from the edge of a feeding area.

A non-aggressive hunting method is used, namely, “skilled stand hunting,” which is much different from the way most stand hunters stand hunt these days.

The hunter scouts 2–3 weeks before a hunting season begins to find one or two mature-buck-effective stand sites per hunter per day to be used during the first 2–3 days of the hunting season.

A mid-hunt scouting method that does not alarm deer, limited to deer trails designated for this purpose during specific time periods, is used to find new mature-buck-efective stand sites daily during the balance of the hunting season until a buck is taken. Vicinities, trails and sites being frequented by mature bucks right now, today, which are very likely to be used again by the same buck later today and tomorrow morning if the hunter does things right (with the posible exceptions of trails) – locations made evident by very fresh tracks, droppings and other deer signs – are searched for daily, selecting promising stand sites along the way without halting, to be used during the next 24 hours, or halting to begin using imediately.

A through knowledge of deer signs and the ability to accurately identify tracks and droppings made by mature bucks without halting to measure them during a hunting season are required.

The spread of ruinous lasting human trail scents in the hunting area must be minimized throughout the hunting season.

Certain proven tactics are used to avoid alarming deer along the way while hiking to stand sites and avoid being positively identified by deer near stand sites.

Precautions are taken to allow whitetails to remain in their home ranges throughout a hunting season.

As silently as possible (best done with a backpacked stool), beginning day three the hunter switches to a new stand site every day or half day (best) 100 yards or more away from any previously used stand site until a buck or other deer is taken.

Dr. Nordberg’s six new hunting methods, introduced in his newly published Whitetail Hunters Almanac, 10th Edition, have all of the elements (above) needed to be mature-buck-effective. Used properly, each of these hunting methods can put you close to one or more mature bucks once or twice every day or half day of a hunt, though you may not realize it until after you find tracks that reveal a mature buck spent some time downwind of your stand site. Do not despair when this happens. After a mature buck discovers you stand hunting (not moving about, which it can detect via smell alone), it will only quit approaching within about 100 yards of where you were sitting. It won’t abandon its range unless you somehow greatly alarm it – an all important advantage provided by stand hunting. Moving 100 yards or more to a new stand site during the following day or half day will put you back in the ball game. The buck will have to find you all over again before it can be safe while engaging in its daily activities. Sooner or later, that buck will be a short distance away, unsuspecting, before it realizes you are taking aim at it.

Be assured, because Dr. Nordberg’s mature-buck-effective hunting methods evolved from more than a half century of scientifically-based, hunting-related field research with wild whitetails, they work. Once mastered, you will soon begin to realize tree stand hunting is no longer the best or only way to hunt mature bucks or other deer. Over the long run a ground level stand hunter usng a backpacked stool and mature-buck-effective hunting methods can outhunt any deer hunter using any other hunting method.

Portable Stump Hunting: the Most Simple Form of Mature-Buck-Effect Stand Hunting

Back when I began hunting whitetails at age ten, stand hunters were commonly called “stump sitters.” Tree stand hunting was unknown then. After fifteen years of being a member of a gang that only made drives, rarely taking bucks older than yearlings, I finally became serious about stump (log) sitting, after which I finally began taking mature bucks. In the 1960s, long before tree stand hunting became known, I began studying and hunting deer from primitive platforms nailed to trees six feet above the ground. After that, tree stand hunting was my favorite hunting method until the late 1980s, then the favorite hunting method of deer hunters all over America, At that time, however, it was becoming obvious mature bucks were learning to identify avoid hunters in trees. For this reason, I then began experimenting with stump sitting again. Real stumps being damp and uncomfortable and rarely located where I wanted to sit, I began using a homemade folding stool with a camo fabric seat, oak frame and shoulder straps, calling it a “portable stump.” The advantages provided by a portable stump, the basic tool for this most simple form of mature-buck-effective stand hunting, are amazing. The following is one of many tales I have written for outdoor magazines) about how my portable stump has provided me with great buck hunting.

It was 5 AM, pitch dark, when I arrived at the spot where I planned to turn straight east a mile north of camp, about another mile northwest of where I planned to sit. The ground level stand site I had in mind was a clump of 4-foot oak saplings with retained leaves beneath a scrubby red oak on a slope overlooking a deer trail discovered while scouting three weeks earlier. Coursing between a large hill west of that tree and a beaver pond east of it, this well-worn trail was full of fresh and old tracks and droppings made by at least two different mature bucks plus several regularly renewed ground scrapes.

The unaltered series of deer trails I planned to use to get there from downwind, illuminated by my flashlight, crossed a saddle near the south end of a high ridge and then dipped down through a low browse area much visited by whitetails during past hunting seasons. From there I followed a familiar, moss-covered deer trail through scattered spruces to the northern tip of a white granite slab of rock more than a quarter-mile long. My intended stand site was at the south end. When I halted there to decide whether I should proceed across that opening or head southeast to a deer trail that curved toward my stand site through dense brush and tall quaking aspens, a yearling doe trotted past without haste ahead of me, tail down, made barely visible by the narrow glow beginning to widen along the eastern horizon, and disappeared into a stand of young aspens on my left.

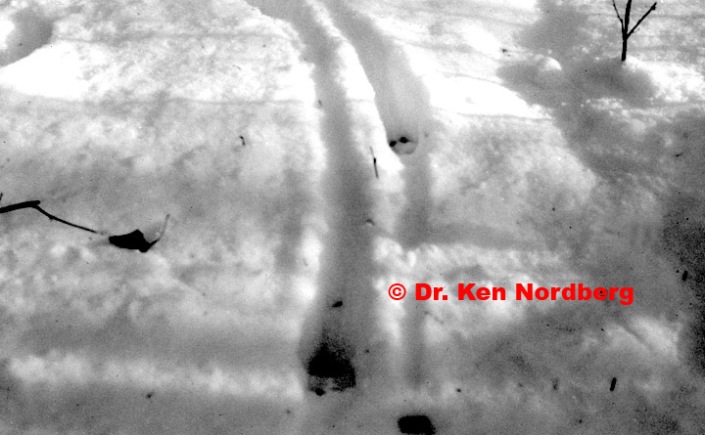

Deer obviously being in the vicinity, I decided to use the trail coursing through the tall aspens. Shortly before finding it, however, I came across a patch of snow about 20 feet in diameter where two mature bucks had obviously battled a short time earlier. Now anxious to get to my stand site as soon as possible, I proceeded at a steady pace into the wind along that deer trail, keeping my head pointed straight ahead (in case any deer along the way were watching me) until about 100 feet east of where I planned to sit. There I halted again upon discovering another heavily tracked patch of snow where the two bucks had obviously battled a very short time earlier. The smell of buck musk was still strong there. About 20 feet to the right of the site of this battle I noticed a splash of black dirt scattered across the snow. Upon taking a few steps nearer, it became obvious it was a very recently renewed ground scrape, surely made by a dominant breeding buck, November breeding being in progress. The scrape was more than four feet in diameter and an overhanging bough of an adjacent black spruce was well mangled, pieces of it scattered across the scrape.

Now excited, I then backed carefully away downwind, soon spotting what appeared to be an appropriate spot to place my stool. After tiptoeing through a dense patch of 4-foot-tall mountain maples, managing to avoid making any discernable sounds, I sat down on my stool with my back against the rough bark of the 2-foot-wide trunk of an ancient aspen and pulled my camo headnet down over my face.

Thirty minutes later, then fully light, I was suddenly astonished to see of the head of an 8-point buck with wide antlers facing me, intently rubbing scalp musk on that ravaged spruce bough only 25 yards away. While slowly leaning to my right, I finally found a narrow, clear opening to the center of the buck’s throat patch and squeezed my trigger. After waiting about five minutes, hearing nothing, I anxiously arose and pushed through the mountain maples toward the scrape. There it was: a beautiful 8-pointer lying motionless across the scrape (see photo above).

There is much to learn about portable stump hunting, the simplest form of mature-buck-effective stand hunting. Learn it all in my newly published Whitetail Hunters Almanac, 10th Edition.

A Large-Group Stand Hunting Method for Taking Mature Bucks

Have you ever hunted a big buck for an entire week, stand hunting at a different site every half day within sight of the buck’s very fresh tracks and droppings without ever seeing it? I have, several times. I knew where this particular buck fed twice daily, a thirty acre lowland dominated by black spruces, tall aspens and alders loaded with favorite winter foods of northern Minnesota whitetails, mainly red osiers. I knew two major routes the buck used to travel daily between its feeding and bedding area, located along opposite sides of a high wooded hill with steep sides. I knew where it bedded, on the commanding tip of a rocky ridge almost a half-mile south of its feeding area. I stayed away from this bedding area because bucks such as this so often discover hunters waiting in ambush near them, their safest refuges thus ruined, after which they are very likely to abandon their entire home range for the balance of the hunting season. Wherever I sat that week, stand hunting, that buck somehow contrived to browse on the opposite side of the feeding area or use the trail on the opposite side of the steep hill. It was uncanny.

On Friday evening when my three sons and a son-in-law returned to camp from college and jobs, asking, “Did you get the buck Dad?” All I could say was, “Nope,” finally adding, “I’ve decided I need your help to get it.” I was somewhat reluctant to say this because whenever I said it in the past, one of my sons got the buck.

The help I had in mind was a large-group stand hunting tactic I created several years earlier called, “Cover-All-Bases Buck Hunting,” Though it always worked, success was dependent on superb forest navigation in darkness before first light in the morning by all hunters taking part. Every hunter had to know exactly how to get to a specific stand site without alarming the intended quarry and other deer along the way. It also required an extensive knowdge of trails and sites currently frequented by a mature buck. In this case I instructed two hunters to stand hunt at certain sites on opposite sides of the of the feeding area and the two others to hunt downwind of the trails on opposite sides of the high hill, leaving the bedding area for me.

It was snowing heavily at first light the next morning when I heard something that sounded like someone had just slammed a large barn door shut, obviously a gunshot. With that, I swung my portable stood to my back and headed downhill toward the origin of the shot, the site taken by my son-in-law. Upon arriving, there, however, no one was there. While wondered where to go next, someone slammed that barn door three times behind me, at the site taken by my son, Ken. This is the Nordberg signal meaning help is needed to drag a buck to camp.

As I rounded the north end of the steep hill, I spotted a sizable bonfire ahead. Next to some branches sticking up left of the fire stood my son, Ken, and my son-in-law. As I drew nearer, I noted Ken was grinning from ear to ear and the branches sticking up were antlers. “My buck,” I murmured, Cover-all-bases had worked again, with the usual dreaded results.

For complete information about when and how to use this large group stand hunting method and why it works so well, go to my newly-published Whitetail Hunters Almanac, 10th Edition.

The Gentle Nudge: using human airborne scent rather than an aggressive hunting method to take big whitetail bucks

Now and then when snow covers the ground, my three sons and I take a big dominant breeding buck using an extraordinary hunting method we developed about 25 years ago, named “the Gentle Nudge.” It began with the discovery of peculiar deer tracks in snow made by a buck under the influence of the airborne pheromone emitted by a doe in heat, the buck dragging its hooves from track to track. If the hoof prints were about four inches in length (Minnesota), they were made by a dominant breeding buck, the largest buck living within the surrounding square mile. My boys named these tracks “railroad tracks.” From that time on we knew such tracks were made by a fully mature buck that was either accompanying a doe in heat (2-5/8 to 3-inch long doe hoof prints accompanying railroad tracks) or the buck was downwind of a doe in heat (no doe tracks accompanying railroad tracks). More importantly, upon first discovering such tracks, we knew that buck would be with that doe in the nearest whitetail feeding area during the first three legal shooting hours in the morning or the last two hours in the evening or in the doe’s bedding area midday during the next 24 hours – the length of time the doe could be expected to be in heat, assuming it began a short time earlier. We always realized, of course, the doe’s heat could have started much earlier, prompting us to always take quick advantage of railroad tracks.

The earlier discovery of the fact that mature bucks are rarely taken by hunters making drives had a lot to do with the development of a new hunting method we decided to use to take bucks under these circumstances. Older bucks generally have three ways to escape drives unscathed: 1) abandoning the area to be driven shortly before the drive begins, 2) outflanking the oncoming drivers, keeping track of upwind hunters via airborne scents and sounds, and 3) by hiding in dense cover between advancing drivers until they have passed. Mature whitetails (not fawns and yearlings) are determined to avoid being driven far in any direction by hunters or predators, especially downwind, apparently expecting an ambush ahead. As soon as they gain a safe distance ahead of an oncoming hunter, they’ll veer right or left and finally turn into the wind to avoid ambushers, thereafter quickly abandoning their home ranges.

Logically, then, upon realizing where a big buck is accompanying a doe in heat right now – in the doe’s feeding or bedding area – rather than attempt to drive the buck toward one or more downwind hunters, almost always certain to fail, I decided to try a non-aggressive approach, using my own spreading airborne scent drifting from a stationary upwind stand location to convince the buck and doe to depart without haste downwind (the key), typically happening on a deer trail toward the undetected downwind stand hunter. The first five times we tried this with me or one of my sons sitting upwind and my son, Ken who discovered the railroad tracks, sitting downwind, it worked perfectly. Three of those first five bucks are now on a wall in Ken’s den. Dominant breeding bucks taken by my daughter Kate and me while using this tactic are looking down at me from my office wall as I write this. To work, certain precautions must be taken while heading to decided locations of stand sites and, of course, the hunter must know locations of nearby feeding and doe bedding areas, provided by knowedgeable preseason scoutings. Done, right, the gentle nudge rarely fails. A big, unsuspecting buck usually ends up near the downwind hunter within one half to four hours. Learn exactly how and when to use this amazing mature-buck-effective, small group, stand hunting method in my newly published Whitetail Hunters Almanac, 10th Edition.

Your Next Favorite Deer Hunting Method: Opportunistic Stand Hunting

Let’s imagine you and I have decided to do some bass fishing. How are we going to do it? Should we put minnows on our hooks, cast them next to a weed bed and sit in our boat at the same spot all day long watching our bobbers? Let’s imagine we caught one. Should we then return to the same weed bed and fish the same way, anchored at that same spot, every day for a week or two and do the same year after year? Of course not. Every experienced bass angler knows a much better way to catch bass. Yet, this is exactly how a majority of American deer hunters have been hunting whitetails since the 1980s. What’s wrong with it? After millions of us have been doing this all these years, annually culling deer vulnerable to such hunting, almost all North American whitetails today that have survived two or more hunting seasons know exactly how to identify and avoid tree stand hunters. Sure, tree stand hunters still take deer (whether using bait or not), but most deer taken by them are inexperienced fawns and yearlings.

Opportunistic stand hunting, evolved from my 55 years of hunting-related research with wild deer, is a new, fair chase (no bait) hunting method akin to fishing for bass the most productive way, moving often. Not as often as bass fishermen, but changing stand sites every day or half day. Moves are not aimless. The word “opportunistic” refers to taking quick advantage of very fresh deer signs that reveal trails or sites being used by one or more specific, unalarmed whitetails right now. If things are done right, that or those deer will very likely use the same trail or visit the same site (a feeding area, for example) again later today or tomorrow morning. The fresh signs keyed on are discovered daily while hiking along a limited number of specific trails (minimizing the spread of lasting ruinous human trail scents) via a method of mid-hunt scouting that does not alarm whitetails (inspired by gray wolves). This puts the hunter close to a desirable quarry once or twice every day or half-day. Stand sites (elevated and/or ground level) used the first few days of a hunting season are selected and prepared 2-3 weeks before the opener. During the rest of the hunting season, additional stand sites are used right away or later the day they are selected or the following morning. Unless the fresh deer signs happen to be close to a stand site selected and prepared before the hunting season began, most are simple but well hidden ground-level stand sites (for use with a backpacked stool) that have certain mature-buck-effective characteristics and require very litle or no preparation. They are always located within sight of those fresh deer signs and are always downwind or crosswind.

Though not as simple a hunting method as still-hunting or making drives, opportunistic stand hunting is by far the most productive for taking mature bucks today (deer most other hunters rarely see). It enabled my three sons and me to take most of the 98 mature bucks we tagged between 1990 and 2017. Most were taken at stand sites never used before during the first two legal shooting hours of the day. Learn all about how to use this new and unusually productive way to hunt mature bucks and other deer in my newly published Whitetail Hunters Almanac, 10th Edition.

Yes, Much of What I Write About Whitetails is Different

Hunters who have never heard of me are sometimes taken aback by the strange and unheard of things I have to say about white-tailed deer and black bears and how best to hunt them. That’s understandable. Few, if anyone, has done the hunting-related research I’ve been doing during the past 55 years. Many terms I use to descibe behavioral characteristics of whitetails are not commonly found in most books or outdoor magazines. When I first began studying habits, behavior and range utilization of wild whitetails and black bears in the 1960s and 70s, I was taken aback too. The first whitetails I studied were doing crazy things I didn’t expect – dominant breeding bucks abandoning scrapes when breeding began, for example, and breeding on New Years Day, year after year, for another. This prompted me to begin studying whitetails in many other states and in different types of habitat to determine whether or not the first deer I studied were uniquely different as suggested by an editor of Field & Stream Magazine. What I was learning turned out to be characteristic of whitetails everywhere, however. Though I’m sure early Native Americans, mountain men and hunters the likes of Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett knew these things, it didn’t end up in books to benefit us deer and bear hunters today. What I was learning as a modernday hunter and researcher was therefore different but so fascinating that field research and writing about my results eventually became my full time work. Though now 83 years of age, after 73 years of hunting whitetails, mature bucks only since 1970, and more than a half century of field research, I still have no plans to quit.

Actually, I began preparing to do this unique kind of research in 1953, earning three college degrees at the University of Minnesota during following eight years: a Bachelor of Arts degree with a major in Experimental Animal Psychology, a Bachelor of Science with a major in Natural Sciences and a Doctor of Dental Surgery. While there, I worked in the Department of Physiology as a Senior Laboratory Technician taking part in kidney research. After returning home after serving aboard a ship in the U.S. Navy during the Viet Nam War, I became a part time Clinical Instructor in Pediatric Dentistry, also overseeing research dealing with rampant caries in children. All this prepared me well to begin my formal independent hunting-related research with wild Minnesota deer and black bears in 1970. Some preliminary studies began in the early 1960s. My initial studies made me an early pioneer and advocate of previously unknown tree stand hunting and first to accurately describe the whitetail rut.

Always anxious to share what I was learning with other hunters, I began submitting articles to many outdoor magazines in 1980. Since then I have written nearly 900 articles about whitetails and whitetail hunting. During the past three decades I have been a feature writer (Dr. Nordberg on Deer Hunting) for Midwest Outdoors Magazine. For many years, I was also a feature Writer for Bear Hunting Magazine and a bowhunting magazine. In 1988 I began writing my popular 10-book series entitled, Whitetail Hunters Almanac (the title now copied by others). Shortly, I will publish my 5th Edition of Do-It-Yourself Black Bear Baiting & Hunting, an upgraded guide to hunting trophy class bruins. This book has long been considered the “Black Bear Hunter’s Bible,” guaranteeing hunting success. It changed the way black bears are hunted all over North America. I have also created several popular videos including a 12-hour series entitled Whitetail Hunters World (no longer available) and videos with my son John’s help from my Buck and Bear Hunting Schools in the wilds of northern Minnesota – attended by hundreds of hunters from all over America for 15 years. I have presented countless deer hunting seminars at sports shows and sportsmen clubs in the eastern half of the U.S.. Today, I also provide hunting instructions on the internet, including website articles, blogs, Twitter and YouTube preentations.

My newly published 10th Edition of Whitetail Hunters Almanac, a 518-page, 8” x 10” encyclopedia of modern whitetail hunting with 400 illustrations introduces six new, mature-buck-effective, fair chase, hunting methods. Though designed specifically to provide easy shots at unsuspecting (standing or slowly moving) older bucks short distances away, they also provide frequent opportunities to observe or take other deer. These hunting methods, including my favorite, opportunistic stand hunting, enabled my three sons and me to take 98 mature bucks between 1990 and 2017, many now on our den walls. When properly used, these new hunting methods are far superior to all other hunting methods for taking the most elusive and wasted of whitetails, bucks 3-1/2 to 6-1/2 years of age. I am anxious to teach as many deer hunters like you as I can to use these impressive new hunting methods.

American whitetail hunters have been misled by many myths and misguided claims that have actually been limiting deer hunting success for 100 years or more. In my new book I disprove commonly believed myths and misguided claims. Everything I teach about whitetails is based only on what 80-90% of each of the five behavioral classes of wild whitetails do under similar circumstances over periods of ten or more years. Limiting my conclusions to this methodology is the only way I know to establish truths about whitetails (and bears and wolves) and develop superior hunting methods. Sure, whitetails are taken lots of different ways, but something that works once or even twice, or a stand site that enables you to take a big buck isn’t likely to make you a regularly successful buck hunter. A tactic like making drives that enables you to take lots of young deer isn’t going to make you regularly successful at taking mature bucks either. Making you a regularly successful whitetail hunter, or better, regularly successful at taking mature bucks only is my goal. Properly done, what I teach works. Rather than doubt it, give it try, sure to be an exciting and rewarding way to prove it.

So, my hunting friends, you now know me, what I’ve been doing for you during the past 55 years and why what I teach is often quite different.

Can Our Whitetails be Saved From CWD?

Maybe you don’t realize how serious this new threat to our white-tailed deer really is. It began in the late 1960s when a strange new disease was discovered killing captive mule deer in Colorado. It was given the name Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) because affected deer eventually lost considerable weight, making their ribs show. Initially, this fatal disease was spread by shipping infected captive deer yet without symptoms (it can take years for symptoms to appear) from privately owned deer farms to different states and countries. Inadequate means of keeping infected captive deer from coming in contact with wild deer then opened the door to passing CWD to free-ranging white-tailed deer, mule deer, black-tailed deer, elk, moose, caribou and reindeer in 24 U.S. states, three Canadian provinces and two foreign countries, including of all places, South Korea. Though stringent new federal and state regulations and diagnostic testing now make it unlikely animals with undiagnosed CWD can be shipped anywhere, this fatal disease has thus far defied all attempts to eliminate or halt its spread among our unfenced wild whitetails.

No American citizens have thus far contracted this disease after handling or eating venison from deer infected with CWD and many researchers believe humans and our livestock are safe from it, but a theoretical risk of humans contracting this disease nonetheless exists. The misshapen prions that cause this diseases can mutate and have. CWD belongs to a group of diseases known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) that include scrapie (fatal to sheep), mad cow disease (fatal to bovines) and relatively rare Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (unrelated to a disease of animals but fatal to a small number of Americans annually). Scrapie has never affected humans, being unable to jump the usual barrier between different species of mammals. From mad cow disease, however, came a new variant of “Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease” which did jump the species barrier from cattle to humans, killing 177 people that ate beef from infected cattle in the United Kingdom between 1986 and 2012. This might not be the end of it. New studies in the UK reveal persons with certain genetics may develop symptoms of this variant of CJD many years after being infected.

Most researchers and organization involved with seeking to stem CWD in North American recommend taking certain precautions when hunting and taking deer in areas where CWD in deer is known to exist. The following precautions include a few additions of my own:

• Do not harvest a deer that appears sick, emaciated (ribs showing) or acting abnormally.

• Whether a deer you harvested had any symptoms of CWD or not, wear latex/rubber gloves (arm-length) when field dressing it.

• Have your deer carcass tested for CWD as directed by your state Department of Natural Resources, thus providing information vital to halting the future spread of CWD.

• When butchering, bone the meat (cut meat away from bone), sawing through no bones, especially the skull or spine (do not split the backbone).

• Avoid handling brain, spinal cord or lymph glands.

• Thoroughly clean your hands and sanitize your tools after field dressing or butchering by boiling them in water for 20 minutes.

• Instruct your meat processor (if you take your deer to one) to bone your meat and package it separately from other deer.

• Consume none of the meat until you have received results of your test for CWD. If positive, destroy your venison as directed by your state DNR.

Personally, I believe our whitetails will be saved, but it may be a lengthy and heartbreaking ordeal for deer, state deer managers and deer hunters. Almost everything imaginable has already been tried to arrest the spread of CWD among wild deer in America, but unfortunately without significant success. Hopefully, some new research will soon find a new way to stop this disease. Success may have to come from whitetails themselves, deer vulnerable to CWD dying and deer not vulnerable to CWD surviving to recreate a whole new population of whitetails resistant to CWD. As mature whitetails have been proving to human hunters for thousands of years, they are amazingly adaptable and persevering animals. I can’t believe some misshapen prions that cause CWD can actually wipe them out.

Meanwhile, unaffected whitetails need to be hunted. Without hunting, healthy whitetails can double in numbers in one year. Nowhere in America can remaining habitat suitable for whitetails support twice as many deer. If allowed to become overabundant, they will suffer from malnutrition and starvation due to a lack of adequate food, especially in winter, making them vulnerable to disease. Our obligations as American deer hunters do not end with the purchase of a hunting license or the threat of CWD. During the coming days and years, we must give those who work to stop CWD our greatest support. They are going to need it.